With more than 11,000 colleagues, Boskalis operates globally in over 90 countries. Every day, these dedicated professionals make a difference in executing dredging, offshore, and salvage projects. One of them is Marco Stuijts, chief engineer of Boskalis’ mega trailing suction hopper dredger Queen of the Netherlands.

With a hopper capacity of 35,000 cubic meters, the Queen of the Netherlands is among the largest dredging vessels in the world. The vessel has been performing at a top level for decades and remains highly competitive compared to similar vessels. “This fact is a great compliment to the colleagues working below deck on the Queen of the Netherlands. It means that we, too, are delivering excellent performance and are safely and responsibly maximizing the ship’s potential. That’s where our pride lies,” says Stuijts.

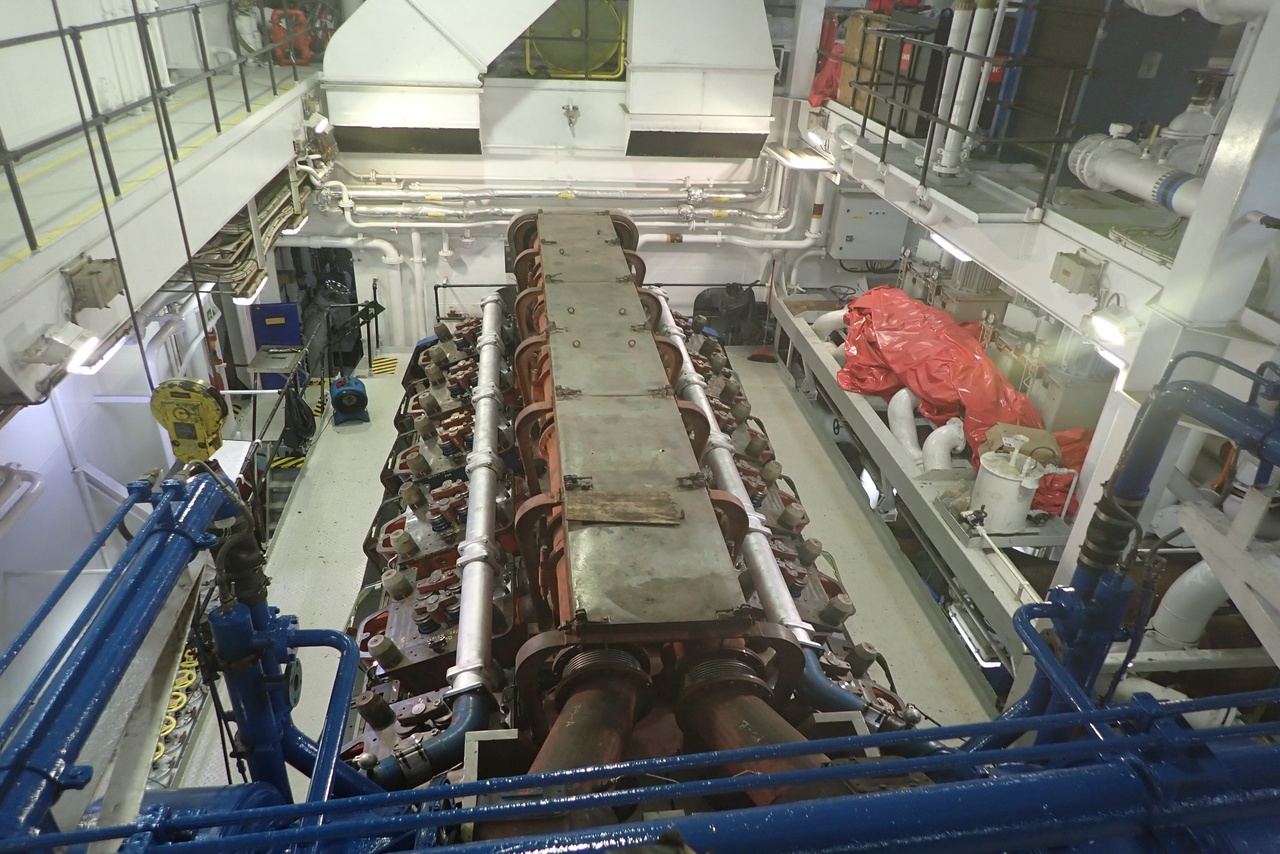

Millions of cubic meters of sand have been pumped ashore by the Queen of the Netherlands since its commissioning. That’s a quantity that excites everyone at Boskalis, including Stuijts and his fellow engineers. But they also literally see the impact that countless grains of sand have on the vessel and the dredging installation every day. As chief engineer, Stuijts is the head of the engine room and, along with his team, is responsible for all technical installations: from the suction pipe to the smallest conceivable gears and from the main engines to the electronics.

In his more than 28 years of service with Boskalis, Stuijts has taken apart and reassembled virtually every component in the engine room of a trailing suction hopper dredger. Now, as the person ultimately responsible below deck, much of his daily work involves administrative tasks. “You review the daily reports of the dredging system’s machinery, fuel consumption, and the many pipelines, the wear of which is monitored using thickness gauges. And you plan ahead, for instance, for future repairs or major maintenance. In recent years, we’ve become increasingly dependent on onboard electronics; everything is digitally recorded and almost automatically documented. That’s a positive development because it gives us more time to focus on the ‘hands-on’ work.”

Motivation

Through this ‘hands-on’ work, engine room personnel aim to optimize processes. This becomes evident, for example, when ordering spare parts. In an ideal world, a vessel would always have every necessary part on hand in case of a defect. However, there isn’t sufficient space onboard the 230-meter-long Queen of the Netherlands. In short, Stuijts and his colleagues make weekly decisions about which parts to order and which not to. “Our experience has taught us that some parts wear out faster than others. We factor that in. The key lies, of course, in the critical components for the dredging process, such as the main engine, a dredge pump, or a jet pump. Do you always want to have these in stock for the exceptional case of a defect? Or do you take the risk, knowing that in the unfortunate event of a failure, you could face significant downtime? That assessment and analysis are not up to us. The decision is made by specialists at headquarters. However, as engineers, we’re certainly involved in the discussions. These are always interesting and educational conversations.”

Stuijts’ day onboard starts around 5:15 AM. His first action: having coffee on the bridge with the captain, the dredging master, and the vessel’s electrician to discuss any technical developments that occurred onboard during the night. “Nowadays, everything is digitally recorded, and we have a lot of electrical measuring equipment onboard, so it’s crucial that the vessel’s electrician is part of that conversation. Afterward, I head below deck and brief the team. Once they’re informed of the current situation, I always take a tour of the engine room. Not to check everything, but to see with my own eyes how the vessel is doing. It’s something I still find fascinating and rewarding to do every day. We mustn’t forget that at Boskalis, we get to work with exceptional machines and vessels on extraordinary projects.”